Coronavirus: "After the black plague, medieval society did not learn from the crisis", recalls the historian Claude Gauvard

In the 14th century, the black plague fell on Europe and ravaged medieval society.In a few months, "the beast", as it is then called, decimates whole villages, kills tens of millions of people, between a third and half of the world's population, according to estimates.It was more than 600 years ago and yet, the "large plague" offers interesting lighting on the coronavirus pandemic, which has touched the world today for several weeks.

"We are not so different from the people of the Middle Ages," says the historian Claude Gauvard.20 minutes questioned this great specialist in medieval society, a member of the Western medieval laboratory in Paris.

The COVVI-19 appeared in China before touching the entire globe.Where does the black plague come from?How did she spread?

Probably Asian, but it is difficult to know the country of origin.Some sources say that during a siege in Caffa [Genoese port on the edges of the Black Sea Crimea], Mongols launched sick bodies over the walls to reach the inhabitants, like a biological weapon of war.We know that the plague is imported into the West by a Genoese ship, which notably accosted in the port of Marseille in 1347.

The disease spreads to the West at very high speed, by land transport.The ascent is carried out by the Rhone furrow and spreads everywhere, in the Empire (current Germany), the current Netherlands, but also England.In one year, the whole West is affected, except for a few mountainous regions such as Béarn.

At the time, there was no planes or cars like today ... How to explain this rapid spread?

We sometimes wrongly imagine a medieval static population.However, all the economic fabric is done by the roads, the paths, through the markets, the fairs.There are a lot of contacts.Unlike us, they live with each other, with a higher sense of the community, family ties.When they are sick, instead of dying locked up at home, they find their loved ones.

There is the example of this merchant, the widow Bouret, who lives in Trigny, in Champagne, and realizes that she caught the plague: "On the way, the beast took me," she said.She then chooses to go to Reims to find her family and die with her family, equipped with the sacraments.In the end, she contaminates her mother and son, who died on the same day, "as several of the said city".These population movements allowed the epidemic to spread.

How many deaths has caused?

There are in fact two forms of disease: the bubonic plague [of the nodes are formed after the bites of infected fleas], where some remissions are possible, and a pulmonary plague, which is transmitted by the postilions, which is fatal in 100 %cases.It is estimated that between a third and half of the world's population perished.The first wave of epidemic of black plague lasts up to around 1352, but there are then many pest resurgences, which are sometimes very deadly, until 1720 in France.

How do the authorities react?Is a confinement put in place?

Not immediately.The high spheres of society, as in Florence, can isolate themselves and get out of it, locked up at home, but not everyone is lucky to have servants to seek provisions.It was not until the 15th century that cities closed their doors and prohibited foreigners.Because there is also a strong xenophobia, a search for scapegoats: the Jews, the lepers and all those who are on the fringes of society.

Hospital services are now exceeded.How does the medical world react in the 14th century?

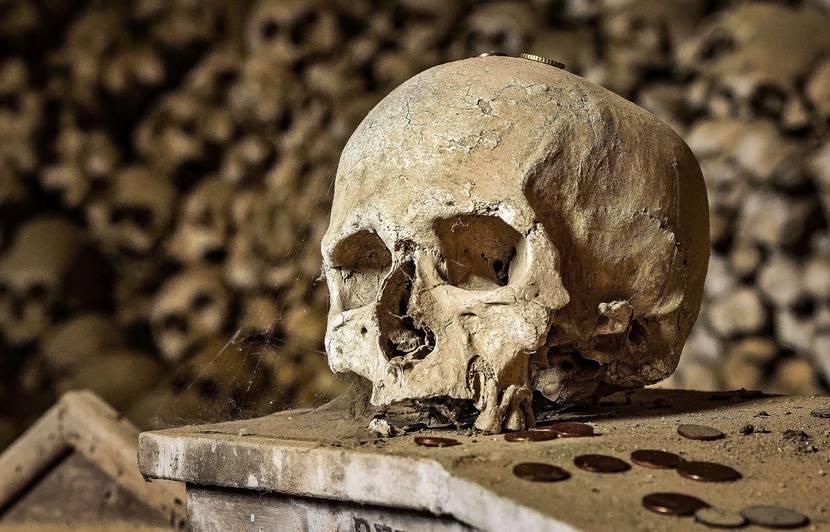

The plague surprises everyone, and there is no concept of what a bacteria or a virus are.We do not know that the disease is transmitted by the chips present on the rats.There are also very few Hotels-Dieu [establishments managed by the Church], which welcome sick and pilgrims.They are overwhelmed, with already three or four patients usually.Mortality is then enormous among caregivers, begging orders, and also in those who bury the bodies.We pile up the corpses, common pits are dug everywhere.

Is fear of death as present as today?

Yes, because the plague is perceived in Europe as a condemnation of God, in the same way as an earthquake or a comet.God punishes the world of his sins.Medieval society is based on tradition, separations between rich and poor, men and women, young and old.But the plague touches everyone.The son no longer necessarily hears the father.There is a great dismay because the social fabric of differentiations is swept and uniformity is perceived as a disorder.

However, isn't the medieval world more used to death?

The medieval population is used to famines, wars, certain diseases, to disappear at 40, 20 years or even before, of course.The "beast" is another anxiety.There is then nothing worse than sudden death, male-mort, bad death, alone, without being able to receive the funeral rites necessary for survival in the afterlife.People are surprised by the plague that they do not know.The last dates back to the 6th century.It's a bit like today: we trivialize the car accident, not the pandemic.

What consequences on society?

We tell ourselves that we must respond to the anger of God, purifying the manners who would have perverted.This means following more divine precepts, having a simpler life, reducing in particular excess tables.This will feed, I believe, the idea of political and religious reforms, until the reform [Protestant in 1517].There is this idea of divine revenge to which we must answer.

A few days ago, Nicolas Hulot mentioned the coronavirus as follows: "I believe that we receive a kind of ultimatum of nature", we are not far from it ...

In effect.This is what British historian Postan explains with this idea: "Nature chastises man for having asked him too much".There was such an expansion in the 13th century, we cleared excessively, so it led to famines at the beginning of the following century.People were weakened and suffered the black plague all the more.The remedy for moralists was therefore a return to the state of nature, more balanced.

There is another consequence.After the black plague, we copulated excessive, in a survival instinct.We have done a lot of children to somehow defend the species.

What were the consequences of all these dead?Today, many are concerned in particular with a drop in economic activity ...

At the time, the production system also stopped.The economy was then essentially based on agriculture, and some villages were almost entirely decimated.But it is more "easy" to take a field than a factory.And at the time, let's not forget that every city dweller is breeder and farmer, he has his little pig, his hens, and can remain.

From a political point of view, these disorganizations have, in the long term, strengthened the emerging state of French royalty.With the large number of deaths, the grip of its institutions has mathematically accentuated on the remaining population.Finally, we learned to die alone.The place of the individual has therefore developed, through the arts in particular and the appearance of the portrait.

Why did the plague remain in the memories?What lesson can it bring to us on the current crisis?

You have to imagine the trauma of the populations.There was no comparable pandemic in history, that's why the black plague remained in memory.The historian that I am knowing that at the time, after the black plague, medieval society did not learn from the crisis, that nothing has really changed.On the contrary, the crisis has developed individualism and exacerbated xenophobia, withdraw.

Some human pillars remain over the centuries and lead to similar reactions.Because man of the 21st century is not so different from that of the Middle Ages.We must therefore hope that the consequences of the current crisis are more positive.

SociétéCoronavirus : La Poste fait un don de 300.000 masques au ministère de l'IntérieurPodcastPODCAST. Coronavirus : Shakespeare a-t-il écrit « Le Roi Lear », confiné, en quarantaine ?